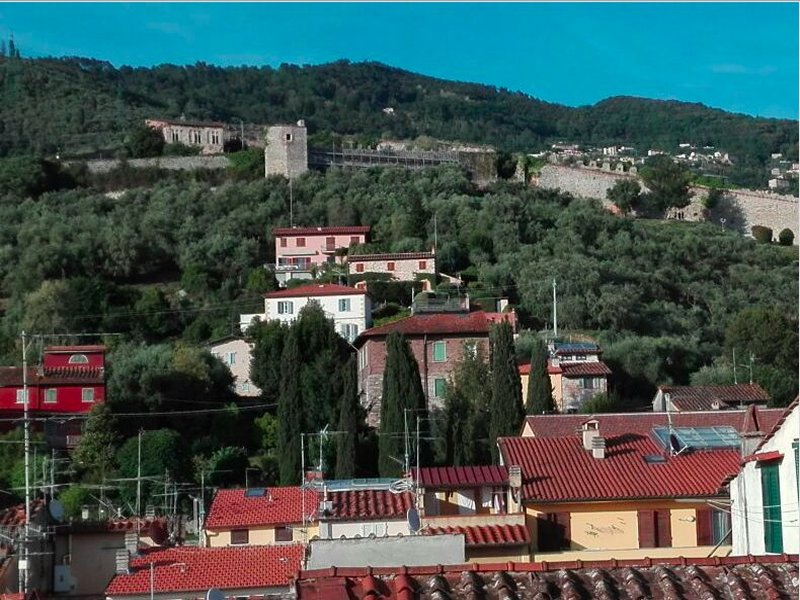

Rocca di Sala

Structure The fortress has a square shape; on the corners there are towers and in the center there was a main tower (or male) with lights and a bell for signaling.

Structure The fortress has a square shape; on the corners there are towers and in the center there was a main tower (or male) with lights and a bell for signaling. There are no signs of rainwater collectors even though the fortress was certainly equipped with them. Below the hill there are two which were most likely used for the fortress. The building was equipped with battlements, drawbridges and moats as can be seen from the drawings and prints by Sercambi, Warren, Gianchi, Mazzoni. The building and towers are mainly made of tuff. There were prisons and other rooms used for this role. The towers changed names and denominations depending on whether the dominion was of Lucca, Genoa or Florence. The complex also included a guard house, a forge and a stable. The fortress was accessed via a large door. The male was divided into three floors (low, medium, high); the one on the ground floor consisted of a large vaulted room supported by a pillar. The first floor was accessed via stairs: here there were three rooms with windows towards the east, towards the west there was a fireplace. You reached the top floor with a stone and wooden staircase. The keep also had the role of a pantry with foodstuffs, supplies, ammunition and also housed a tavern. The first restoration dates back to 1384. Since 2017 the Rocca di Sala has been under restoration to bring it back to its original state: 500,000 euros have been invested by the Province of Lucca. Guinigi Palace In 1408, a noble residence, Palazzo Guinigi, was built inside the Rocca, which hosted several important figures of the time: dukes, grand dukes and notables. Work on the palace continued for several years, the roof was modified with chestnut wood and the loggia was paved. This palace came to be one of the most beautiful architecture in Versilia. Various letters testify to the beauty of the villa, its appearance, its characteristics and the pleasure of staying there. It housed various rooms: the study, the "cambora", the kitchen, a small room, a large room, a sacristy, a chapel, a pantry with oil, an oven and other rooms. In the courtyard of the structure there was a rainwater tank. In 1523 some changes were made to the rooms reserved for soldiers. In 1408, as soon as it was built, it hosted Ladislaus, king of Naples, and his wife Ilaria of Cyprus. In 1437 Nicola di Gio was castellan for the Republic of Genoa, in 1459 Iacopo de Axereto and in 1484, after being at the center of the battles between Florence and Genoa, it passed definitively to Florence which dedicated itself to the restructuring and restoration, not only of the Rock and the walls, but also of the palace. To trace the appearance of the palace and the fortress we can refer to the numerous drawings and prints of the time preserved in the State Archives of Lucca and the State Archives of Genoa. From these documents it can be noted that the big difference between the fourteenth-century complex and that of the fifteenth century is Palazzo Guinigi itself. In 1494 Charles VIII stayed in this place and then Monsignor Marco Antonio di Beaumont stayed here who had come to Pietrasanta to bring help to the Florentines (15,000 men) in the war against Pisa. Pandolfo Acciaiuoli, a Florentine nobleman, and Carlo Dei stayed at the Villa as well as all those who had to view the works for the fortification carried out in those years. In the year 1529, however, we know from some testimonies, this place was already in a state of complete abandonment as described in a letter by Giannozzo Capponi: the building almost looked like a ruin. In 1535 Francesco was castellan of the late Gio Guidetti dei Rucellai. Charles V stopped at the palace in 1536, returning from his exploits in Tunis, and in June 1538 six cardinals accompanying Pope Paul III were guests. The Pope also stopped at Villa Guinigi on other occasions, such as on his return from a trip to Nice where he had gone to carry out some negotiations. Cosimo I, during his mandate, had the opportunity to stop here to monitor the work in the iron and copper mines and to follow the marble extraction phases. It was during this stay that he signed the decree that donated the house on Via del Rosario in the Tuscan capital to Benvenuto Cellini, the great Florentine sculptor and goldsmith, so that he could finish what is now recognized as his masterpiece: the Perseus. Cosimo I certainly stayed here in 1542, in November 1551 and in the spring of 1560, 1561 and 1562. The officials were ordered that the roads that go to the Rocca "be well arranged so that the water cannot damage them or take them down the terrain of them, making them well convenient, so that it will be as easy as possible for Our Most Excellent Lord, and his lords and courtiers to go to the said fortress as everyone knows, mto usually stay when she comes to Pietrasanta”. In 1552 Pietro da Volterra, Captain Borghese and Girolamo Albizzi were castellans who carried out work not only on the Villa but also on the walls, fixing the drawbridges, wooden doors and towers. Starting from 1954, there began to be fear of a possible invasion by the Turks with the consequent fortification of the entire city walls, the Rocca and the Rocchetta. In 1607, under the tutelage of the castellan Aurelio Lante (news obtained from his tombstone located in the Church of San Francesco in Pisa), the roof was redone. In this period the palace housed a large room on the ground floor containing the cannons, with old-fashioned windows, equipped with marble columns, and the floor was made of bricks. Then there was a second large room that served as a corridor, a room on the east side and a sort of basement that was used to contain rubbish. On the west side there were three rooms. All the floors were made of terracotta which allowed the heat from the fireplaces to be retained and had an insulating function in winter. The wooden ceiling was made up of beams and arches. The 1496 inventory describes a loggia, equipped with covered windows and marble columns with capital bases. Outside, Palazzo Guinigi had a small paved square that included the entire facade; there were several pools for collecting water, some covered with marble, and a rather deep well equipped with four small windows that had the purpose of collecting water. The tanks had a truly remarkable size for the time: the so-called "booty" had a diameter of 11.65 metres. Outside, on the west side, a staircase with 26 stone steps led to the first floor. At the entrance there was a bell and a corridor, from here one door led to a small room where it was possible to change, from another one went directly into the lounge. The latter had five large windows overlooking the garden and on the opposite wall there were four commanders' emblems. From this room there was access to a small triangular-shaped chapel whose condition, however, was already very bad in 1496; there was a small marble altar with a stone set and some pictorial representations of saints in poor condition. On the west side of the hall there was access to a bedroom and a living room with large windows that allowed light to enter. From the western room you then moved on to a room used as a pantry, with a window facing north. The living room communicated with four rooms, the kitchen had a small pantry also with a window and a large stone oven. Inside the complex there was a garden with citrus plants inside which there was a stone house that collected the water and distributed it inside the tanks. The palace and the courtyard were protected by the guards: their quarters were in fact located on the front side. If we compare Warren's 1749 plan and Mazzoni's 1784 plan, we deduce that the building was partly demolished due to its dilapidation. Today only a very small part remains in a state of complete abandonment. You can still identify the arches of the portico, the water leaf capitals, the pillars and the vault. History The origins The Rocca di Sala was probably built by the Lombards to defend the small village of Sala, located along the ancient Via Francigena, which in the 13th century, at the foundation of Pietrasanta, will be joined together with its fortress to the newly formed town of Versilia. In 1324 the fortress (called the upper fortress or also the Ghibelline fortress) was strengthened by Castruccio Castracani, Lord of Lucca, to fortify the Lucca stronghold of Pietrasanta. For the same purpose, Castruccio also had the Rocchetta Arrighina built downstream. According to the Narrative of Pietrasanta, the fortress was instead begun by Arrigo Castracani degli Antelminelli, son of Castruccio Castracani. To confirm this, there are two plaques above the tuff door of the fortress which show the Castracani coat of arms and the Imperial Eagle. The work on the fortresses was completed by 1329. The fortified complex is square in shape, with corner towers and a central keep four floors high, with a bell and lanterns for signaling placed on its top. The entire structure of the fortress was surrounded by a moat equipped with drawbridges; its front side facing the sea and Pietrasanta was fortified by a further enclosure wall defended by three other towers, which housed the entrance door to the entire defensive complex. In 1408 Paolo Guinigi, leaning against the fortress, had one of the most beautiful palaces in Versilia built. Numerous famous people will be guests there: in addition to Paolo Guinigi (1408), the King of Naples Ladislao and his wife Ilaria da Cipro (1 409), Charles V (1536), Pope Paul III (1538), while in the central keep, in the previous century, Emperor Charles IV of Bohemia and his wife had stayed. From the Republic of Lucca to Florence From 1400 to 1428 Pietrasanta lived rather peaceful years under Paolo Guinigi, lord of Lucca. In 1430 Lucca was at war against Florence and found itself forced to ask for help from Genoa: the pact provided that, if within three years the people of Lucca had not returned the sum of 15,000 gold florins, Pietrasanta and the Port of Motrone would have entered into possession of in Genoa. At the end of three years there was a revolt on the part of the Pietra Santini people who no longer wanted to be part of Lucca; after years of conflicts and numerous rebellions they independently passed under the Republic of Genoa in 1437. Florence conquered Pietrasanta at the end of 1484. From this moment a series of fortification works began on the fortress which was the most difficult part of Pietrasanta to conquer, in fact the Florentines themselves had managed to obtain it during the war since the soldiers and notables who had retreated there surrendered, opening the doors . A series of letters between the Dieci di Balia, the magistracy of Florence, and Ristoro d'Antonio di Salvestro Serristori, a Florentine prior who lived in Pietrasanta, testifies to how important the Rocca was considered for the defense of the city and the territory. From these exchanges of letters we also obtain information on the conditions of the fortification which did not appear to be particularly damaged after the war. The official works began on May 1, 1485 and were entrusted to Francesco di Giovanni di Francesco known as il Francione and Francesco d'Agnolo known as La Cieccha. These two Florentine masters had already been commissioned to renovate various walls; Cieccha had also participated in the conquest of Pietrasanta. The Florentines wanted to make Pietrasanta a fortress worthy of the Republic. For the walls they tried to join the old ones to the new ones, fortifying them. Francione and Checca were well paid but had the burden of finishing the work within a year, otherwise they would have had to pay a fine of 300 large gold florins. The fortress was completed on time. Workers from Florence and from near and far countries contributed to the work: stonecutters, carriers, laborers and trowel masters. The most precise information on those who contributed to these works is deposited at the Opera di S. Maria del Fiore but was submerged by the flood of 1966 and is therefore not yet available for consultation. Francione complained to the Ten about delays and about not being able to keep all the workers, which caused some delays in the work. The fortress of those years therefore hosted a large number of workers and also their animals. The towers were modified according to new designs, giving them a round shape, more in keeping with the military progress made at that time and the new assault techniques. During the First Italian War in 1494 Pietrasanta was handed over to the King of France Charles VIII by Piero de' Medici, son of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Subsequently the city and its fortress were resold to the people of Lucca for the sum of 29,000 gold ducats (a figure which fluctuates slightly depending on the sources and documents) by the Duke of Antragos, governor of Italy for the King of France. In the following period the city had several masters. Finally in 1513, with the award of Pope Leo It was a peaceful period for this area, the iron and copper mines and the marble quarries were reopened by Michelangelo Buonarroti. Furthermore, extensive reclamation works were also carried out on the coast thanks to Cosimo I dei Medici. In 1778 it was sold, given that it was no longer useful from a military point of view, by order of Leopold to the Cav. Andrea and Gio. di Dio Luccetti, from Pietrasanta, for 950 scudi.

Share on:

Diventa Redattore!

Vuoi diventare redattore di Pietrasanta.it?

Potrai scrivere articoli sul tuo paese, gli eventi, le manifestazioni etc...

Inviado questa richiesta ci autorizzi a contattarti per maggiori informazioni.

I tuoi dati saranno trattati come previsto dalla privacy.